Anoushiravan Dadgar High School in the Life of Mehri Akbari

Anoushiravan Dadgar High School holds a distinguished place in the history of Tehran—not only as an educational institution but also as a vital chapter in the narrative of this land. Each brick and column of this establishment tells stories in which individuals like Mehri Akbari have played a prominent role. For her, Anoushiravan Dadgar was more than just a school; it was the foundation where her artistic vision began to take shape—a space where her creative potential flourished within a cultural and egalitarian environment.

Origins and Foundations

To understand the role of Anoushiravan Dadgar High School in Mehri Akbari’s biography, it is essential to trace its roots. For centuries following the Arab conquest and the establishment of Islamic governance in Iran, the Zoroastrian community endured various forms of discrimination. Adhering to their ancient faith, they were compelled to pay the jizya—a tax that was not only economically burdensome but also symbolized their inferior social standing. Many Zoroastrians sought refuge in cities like Yazd and Kerman to preserve their identity in relative isolation.

Amid such adversity, the figure of Erbab Keikhosrow Shahrokh, born in 1875 in Kerman, rose to prominence. A devout Zoroastrian and ardent patriot, Shahrokh became one of the most influential figures of modern Iranian history. He served as the Zoroastrian representative in the National Consultative Assembly (Majles) from its second to eleventh terms, dedicating over three decades to the betterment of his community.

Her most significant achievement was the abolition of the jizya in 1929—a milestone that relieved the Zoroastrians from a great financial burden and ushered in new prospects for equality and civil rights. This success was the result of years of negotiations with Qajar officials, backed by the support of wealthy Parsis in Bombay and British influence. The event represented not merely a legal triumph, but a reclamation of human dignity.

Shahrokh’s vision, however, extended beyond legal reform. He recognized education as the cornerstone of real progress. In an era when modern schools were rare and access to education was limited, he emphasized the importance of establishing educational institutions, especially for girls. Deeply rooted in the Zoroastrian belief in gender equality, Shahrokh prioritized girls’ education. This philosophical and cultural foundation gave birth to the idea of Anoushiravan Dadgar High School.

Laying the Foundations of Knowledge and Culture

The urgent need for a dedicated high school for Zoroastrian girls in Tehran became increasingly apparent. Following the completion of Firooz Bahram High School for boys in December 1932, attention shifted toward establishing a similar institution for girls. Representing the Tehran Zoroastrian Association, Shahrokh corresponded with Ardeshir Ji Reporter, the Times’ correspondent in Iran and a prominent Parsi from India. This plea was met with a generous response from Ratnabai Banaji Tata, a benevolent woman of priestly descent from India.

Ratnabai, herself a descendant of Zoroastrian migrants to India, deeply understood the importance of education and empowerment. She pledged a generous sum of 100,000 rupees for the construction and furnishing of the high school, contingent upon the provision of land by the Iranian government and the Zoroastrian Association. Though Ratnabai passed away in December 1930 and did not live to see the results of her philanthropy, her name and noble intent became permanently associated with the school.

After her passing, the Tehran Zoroastrian Association held a grand memorial and pursued the school’s construction with utmost dedication. Ratnabai’s aunt, Nawazbanoo Tata, further pledged an annual donation of 3,000 rupees for the school’s maintenance and support. This continuity of goodwill and commitment to knowledge laid the firm foundation of Anoushiravan Dadgar High School and transformed it into a beacon of enlightenment and hope.

Architectural Expression: A Blend of Ancient Identity and Modernism

Designing a building of such significance required an architect capable of expressing its cultural identity through structural form. The task was entrusted to Nikolai Ivanovich Markov, a Georgian-born architect. Born in 1882 in Tbilisi, Markov studied architecture and Persian literature before migrating to Iran, which he regarded as his second homeland. Passionate about Iranian culture and architecture, his works presented a masterful blend of modern and classical European styles interwoven with authentic Persian motifs. His signature brickwork, known as “Markov bricks,” became emblematic of his influence on Tehran’s urban landscape. Among his notable educational works are Alborz College and Firooz Bahram High School.

Markov’s design for Anoushiravan Dadgar was a striking example of this thoughtful fusion. The grand entrance with tall columns and bull-headed capitals, the Faravahar emblem crowning the façade, and the crenellated roofline all evoked the grandeur of Achaemenid and Sassanid palaces. At the same time, the use of arches in windows and a brick façade reflected the aesthetics of post-Islamic Persian architecture.

More than a school, the building stood as an architectural statement—a declaration of Iranian identity rooted in ancient heritage yet forward-looking. For Mehri Akbari, who would later express herself through lines and colors and transform the canvas into a window of dreams, this architecture might have provided her earliest, subconscious lessons in composition, form, and balance—lessons that would blossom in her art like hidden seeds sown in the fertile grounds of that building.

A Living Space and Lived Experience

On September 10, 1936, Anoushiravan Dadgar High School officially opened. The inauguration, attended by government officials and members of the Tehran Zoroastrian Association, marked the beginning of an institution that quickly became one of Tehran’s most respected educational centers. Unlike many schools of the time that served exclusive groups, Anoushiravan Dadgar embraced all children of the land, regardless of background. This inclusive vision fostered an environment where diverse talents grew side by side in mutual respect and equality.

One of the school’s most notable moments was the enrollment of Princess Fatemeh Pahlavi in 1939 —a testament to its academic excellence. Her mother insisted on strict adherence to school rules and absolute equality, underscoring the value of fairness and discipline. This principle left a lasting impression on all students.

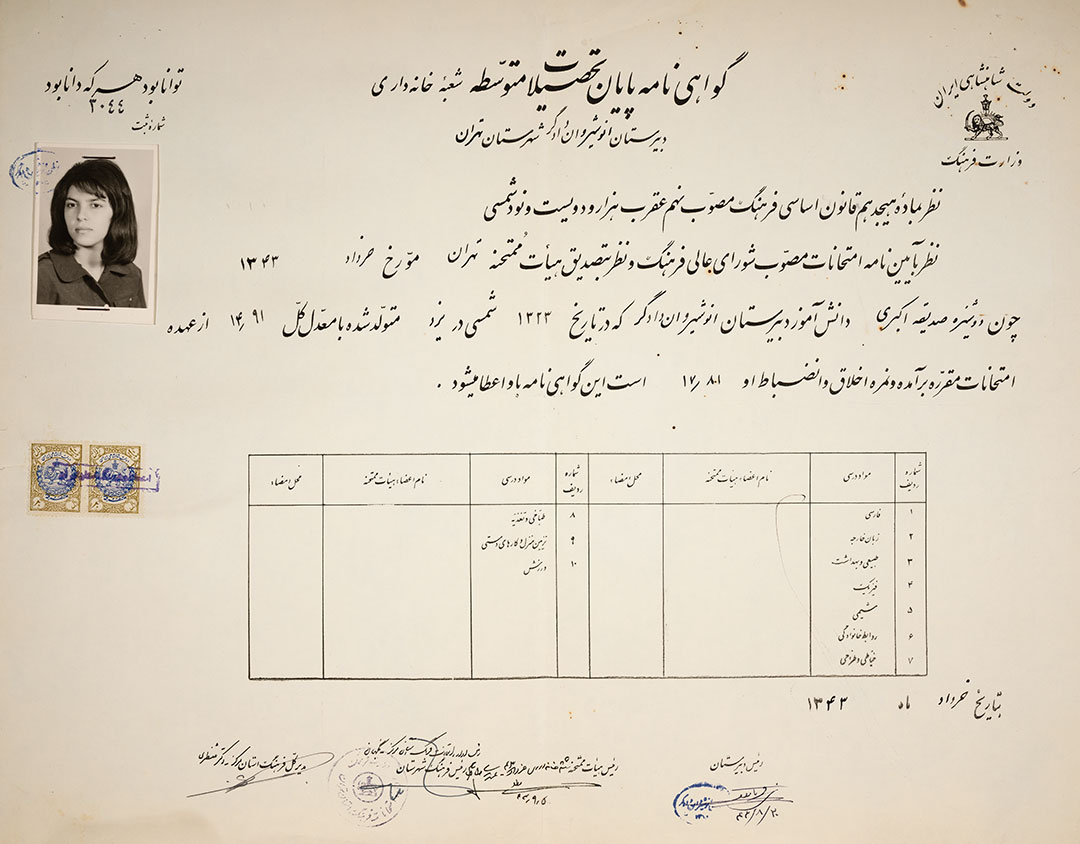

Among those who grew and thrived within its walls was the young Mehri Akbari, alongside other notable alumnae such as Mehrangiz Dowlatshahi (diplomat and ambassador), Shirin Ebadi (lawyer and Nobel Peace Prize laureate), Alenoush Terian (first female physicist and mother of Iranian astronomy), Goli Taraghi (writer), Katayoun Mazdapour (linguist), and Mansoureh Ettehadieh (writer and historian). In the courtyard of this school, she witnessed daily competition and collaboration among her peers Music, sports, and even cooking classes were not merely skill-building exercises—they cultivated taste, precision, a spirit of competition, and discipline.

Despite the passage of time and numerous challenges—including a fire in the 1980s and maintenance issues—Anoushiravan Dadgar High School has stood the test of time. Registered as a national heritage site in 2001, it remains a symbol of a community’s determination to preserve its identity and culture It also represents the transformative power of knowledge and equality, leaving a profound imprint on the development of individuals like Mehri Akbari.